Let it go.

Before it became a Disney song that played on a loop in your head, it was a glib remark, typically delivered with a judgey side of eyeroll. How annoying is it to hear these words? Without exception, my inward response has been: “I’ll let it go in my own damn time.”

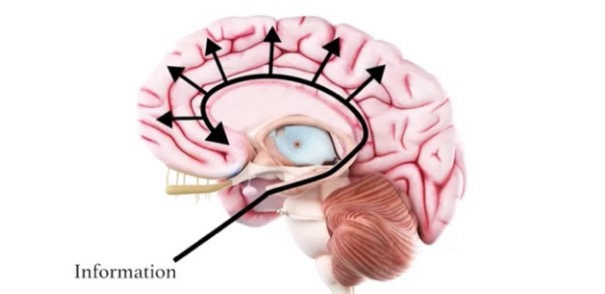

But guess what? We actually can let stuff go, once we are aware it’s a choice. Just this week, I learned that a feeling, positive or negative, lasts for only ninety seconds.* A chemical process occurs in the brain and it takes that amount of time to work its way through the body.

When the ninety seconds are up and you continue to feel the anger, sadness, or fear, it’s a sign that you have chosen a thought that is re-stimulating the circuitry. The thought, not the emotion, is what causes the physiological reaction over and over again.

Why would we do this to ourselves? Because telling stories is how we humans make sense of the world. We build a narrative around the emotion. We connect our past experiences to the feeling and voila, we continue to suffer. Once the emotion has a deeper meaning, we can then cling to it until we drop dead.

The better news is, we don’t have to make up awful stories and continue to feel bad. We can stop ourselves in the act of creating a story after the feeling has passed. And now that I know it’s an actual choice, I am determined to let stuff go like a champ.

I tested this theory last night at the children’s hospital. My son, an avid skateboarder, has rolled each ankle and been x-rayed so many times that Gerardo, the x-ray tech at urgent care, seems more like extended family. I’d noticed that the slight limp after Finn skated all afternoon in front of our house hadn’t resolved. We are a week away fom skateboard camp. I decided we should go in one more time to see if he’d receive the same advice as always, stay off it for a week.

“It’s a fracture,” said the doctor. “You should cancel camp.”

We both crumpled. He needed this camp. He is the baby of the family and Covid has been the least tolerable for him. Starting middle school where he knew no one was particularly cruel to a kid during the masked-up pandemic. On top of that, everything he’d looked forward to for the last year had been cancelled. All except for skateboarding camp.

But also, I needed this camp. A portion of my brain has been on high alert for him all year. I’d put off my big revisions and book proposal until the weeks he would be taken care of by someone other than me. At camp.

I can’t ever get time to do my own work. Everyone else matters more than me. My work doesn’t matter. I don’t matter.

And then I caught myself. I had done exactly what one does to cause suffering in perpetuity. I had attached a crappy meaning to the feeling. I had chosen to be preoccupied by my son’s every move and pushed all the work to the three emotionally-free weeks in my calendar. Intellectually, I know he has his own path and he will be okay. I don’t need to use him as an excuse not to get my work done.

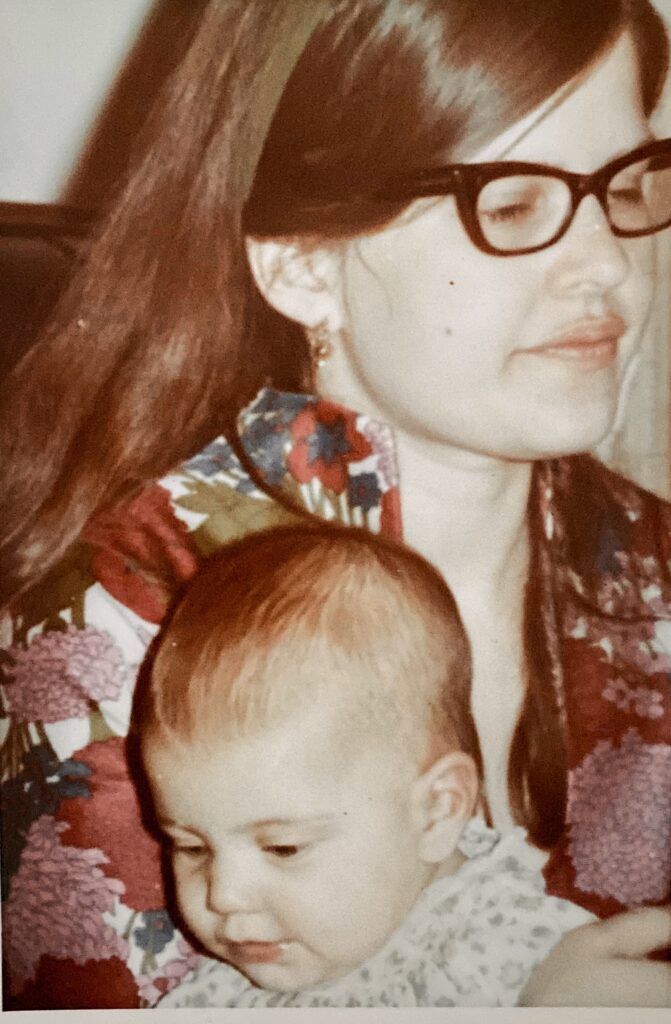

Once I realized I had turned his injury into a story, I noted the familiar theme. I don’t matter. That was an ancient one for me. My story around self-worth goes back to my mother. She left us and I took it personally. As a twelve year old kid, I figured I wasn’t enough to stick around for. And that is what I need to let go.

I wondered if the ninety second thing could conquer this emotional mountain. I called in an expert to ask. Relationship therapist and friend, Linda Carroll emailed me some advice.

The ninety second rule doesn’t count for grief.

When you think about your mom, and the chemicals fire for ninety seconds, what do you do next? How do you minimize or maximize the feeling? Both ways are trouble. Can you allow it like a wave and then continue on? Allow it and make it your Tonglen. It’s a Buddhist practice for empathy where you take in the suffering of someone else and sending them back what they need to heal.**

I try not to think about my mother at all actually. When I do it’s more like an empty cavern inside me than actual emotion. My feelings about her are so desolate even I don’t want to hang out in that place with myself anymore.

As I sat in my writing chair overlooking the quiet backyard, I closed my eyes to try the Tonglen. On the in-breath, I inhaled her sadness as the eldest of seven. The one who heard the stranger say to her mother, “you have lovely children. Each one more beautiful than the next.” As the first child in the row, she took that to mean she was the least beautiful. I breathed in her urgent need, at the age of thirteen, to leave a home ruled by a violent, alcoholic stepfather. Then to escape a lonely, faithless marriage, leaving behind her four children. My chest filled with the torment of damaged relationships with me and my brother and sisters.

The darkness filled me and I sobbed out loud. My heart began to pound as I struggled to turn her pain into loving energy, pink and airy, and send her back light and healing. I was shaky, but I did it. When it was over, all that remained was sadness for her.

I know grief for the relationship won’t disappear in one go, but the exercise opened space for compassion. I felt something for a mother I have felt very little for since she ran out on our family back in the eighties. I will do anything to unburden myself. I don’t want to create distance between me and the rest of the world in service to the story of my mother.

When you let go of fear and open yourself to empathy, you get the sense that it’s all going to be okay.

Love,

Elizabeth

*https://onebodyinc.com/the-90-second-rule-you-cant-afford-to-ignore/

**https://www.lionsroar.com/how-to-practice-tonglen/

If you don’t subscribe to my Friday stories, please do at elizabethheise.com, follow me on Instagram @elizabethheise1 and Twitter @heiseelizabeth1. Thanks for reading.